Know your customer

The people we serve are the lifeblood of our organizations. They’re the reason we design products and services. They pay our bills. They make us laugh, smile—and sometimes they turn our smiles upside-down.

But that’s okay. They’re our customers.

Although this is the case, it’s astounding how often organizations showcase little understanding of the people they serve.

As designers, we’re empowered to change that. We have the skills, and hopefully the support, to engage in a research and design process that gets us close to the people we aim to serve.

“Why do so few organizations understand their customers?”

But how do we achieve this?

It’s different for every team, but some methods are more effective than others. This article is about those methods. In just 3 simple steps, you can get to know your customer better than ever before. Using this foundation, you can design new products and services that create value, meaning, and engagement. These products and services will capture hearts, minds, and wallets.

Where to start

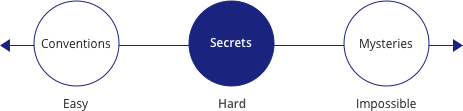

In some cases, you might think you’ve uncovered a secret—something few people know to be true. This might be your advantage. This might help you create value, meaning, and engagement for the people you serve. It may help you competitively differentiate.

But in reality, few design teams operate based on secrets. Hypotheses developed from the synthesis of various information sources are more likely your guiding star.

Yet there are times when we’re stuck. We may not have a clear hypothesis, and we need to go out into the world and discover. We need to learn, and we need to get close to our customer. This is where Jobs to be Done enters the picture.

Jobs to be Done… again

I’m not the first—nor will I be the last—to write about Jobs to be Done. But rather than a rally cry for support if you’re an advocate, or writing me off completely if you’re not, I propose you take the time to read. Then do the only thing that matters: put the process to the test.

“Knowing your customer and their Jobs to be Done also means knowing your competitors.”

With that out the way, let’s start with a quick introduction.

Jobs to be Done (JTBD) is a framework for assessing market opportunity. It helps you better understand what motivates people. It helps you learn about the process people go through to get something done. It provides insight into the situational context people find themselves in when looking to solve a problem they have. In JTBD terms, this is called “hiring.”

Anthony Ulwick, Founder and CEO of Strategyn, first developed the concept of Jobs to be Done. It was later popularized by the likes of Clayton Christensen, Harvard Business School professor and author of The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Here’s a great explanation of the basic theory:

The concept can easily be thought of as the outcome someone is looking to achieve. Jobs are solution agnostic. To provide an example unrelated to milkshakes, people all around the world got up out of their bed today and went into a place they call “work” to do something they call a “job.”

Each one of these people had different motivations. For a few, they’re truly passionate about what they do. It’s almost a gift to be getting paid for spending time on things they love to do. For a much larger group of people, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs came into play.

Working a job is one way to earn money. But earning money for the sake of it is not likely the primary motivator. Supporting a family, putting food on the table, going away on a yearly vacation—these are the outcomes that motivate people. Think of these outcomes as the main Job to be Done.

Before explaining how you can put this to use, it’s worth breaking down the different types of jobs within the JTBD framework.

The different types of jobs

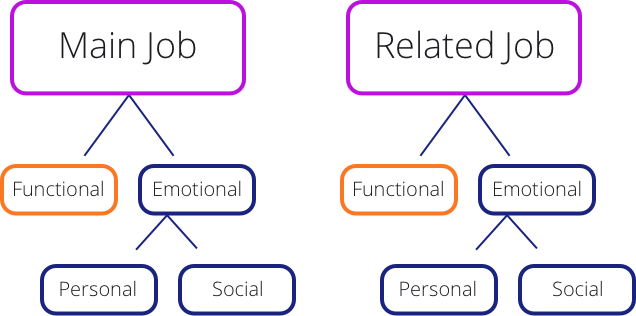

As far as jobs are concerned, there are 2 core job types.

There are main Jobs to be Done. Main jobs describe the higher level outcome people are motivated by.

Using the example above, a main job might be summarized as “support my family.”

There are also related Jobs to be Done. Related jobs describe jobs that support or contribute to the higher level outcome a person is motivated by. These related jobs are often pre-requisites—tasks that assist the overall process and outcome.

Continuing with our example, related jobs might be things like, “get my kids into a great school” and, “renovate the backyard so there’s more room to play sports.”

Jobs can then be broken down further. From these 2 core job types there are 2 additional categories.

There are functional aspects to jobs. Functional aspects are practical, objective requirements that must be met to fulfill the main or related job.

Again using our example, a functional job might be something like, “save an additional $22,000 by Christmas Eve.”

There are also emotional job aspects. Emotional aspects are subjective. They relate directly to how the process of achieving a job, or actually fulfilling the job, make the person feel.

And from that, we have our final layer. Emotional job aspects can be further broken down into 2 dimensions.

The first is personal. This relates to how the person feels. This dimension is intrinsic in nature.

A personal job aspect, using our work example, might be something like, “feel more confident at work.”

The second is social. This relates to how the person believes they’re perceived. This dimension is extrinsic in nature.

Using our example for the last time, a social job aspect might be something like, “have my colleagues perceive me as an innovative leader—someone they can trust and rely upon.”

Understanding the subtle nuance and complexity of the jobs people want to get done will help you get close to the people you wish to serve as customers. It’ll help you design better products and services. It’ll help you differentiate from competitors by fulfilling jobs in new and unique ways.

Here are the 3 simple steps you can take to get closer to your customers than ever before. So when you’re out of secrets, or you simply want to create new customer value, use these 3 steps to help define what the people you serve really care about.

Step 1: Uncover the job

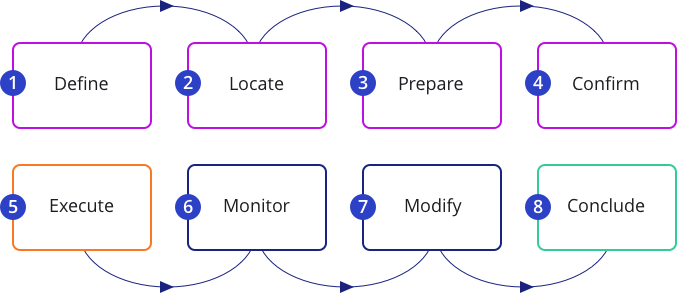

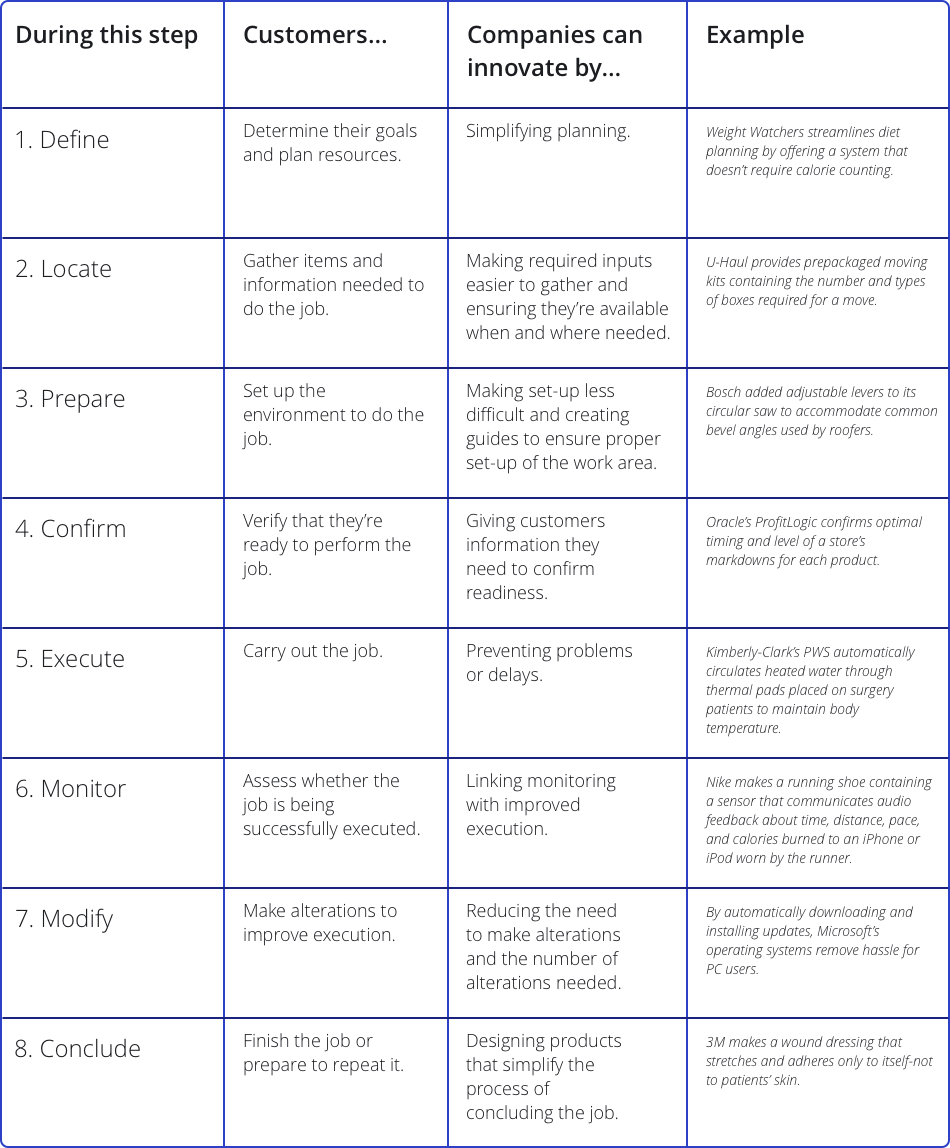

This is where your targeted discovery work begins. It’s targeted because it’s informed by strategy. It won’t be your typical qualitative research effort. You’re going to learn about the things a person wants to happen at each stage of the 8-step job process.

This process is often referred to as job mapping. A job map will enable you to establish a clear view of the steps someone is trying to execute in the process of fulfilling their job. These steps are considered universal.

Developing a deep understanding of what success looks like through the eyes of your customers is the goal of this exercise. You want to understand what success looks like for the job, as well as each of the 8 job steps.

By conducting targeted contextual inquiry research sessions, you’ll end up with documentation that clearly articulates the job and each of the 8 job execution steps.

You’ll want to start off developing your understanding of the execution step—this is the core thing you see. It’s also the thing the customer will most closely associate with the job. As a result, it’ll likely be the easiest for them to articulate.

Then you’ll work through the pre- and post-execution steps to further develop your understanding of the role they play in the overall success of the job.

Rather than guiding you through each of the 8 steps in detail, I suggest reading this HBR article, The customer-centered innovation map, from Strategyn. Their overwhelming rate of success taking new products and services to market should be enough of a reason to click blue.

Executing this process is going to give you a view of people you’ve never had. You’ll have clearly defined success criteria for each of the 8 job steps. Better yet, you’ll have a view of what’s standing in the way of those steps. This is your opportunity.

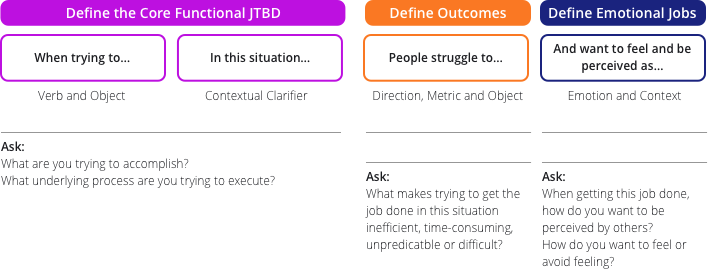

From this baseline, you’ll then develop simple job statements that capture the gist of each job you discover. You can use the template below to do this.

These high-level statements will help you categorize similar jobs. They’ll give you a simple view to work from, and they’ll make your prioritization efforts a whole lot easier.

And that brings us to the next step.

Step 2: Define the job that matters most

Not every customer job can be fulfilled—certainly not by you. So it’s time to focus on the highest value customer jobs that also align to your strategic priorities or market strategy.

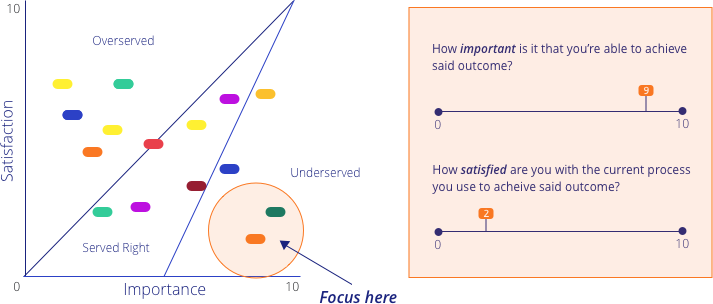

To do this, various techniques can be used. Amongst the simplest is an attitudinal survey of a sample group of customers. This can be based on a Likert scale. By plotting the average scores on a graph like the one below, this effort will help you understand how important a given job is in the overall context of someone’s life, versus how satisfied they are with the way that job is currently fulfilled.

To generate these results, you’ll ask the people involved in your research efforts 2 questions:

- How important is it that you’re able to achieve said Job to be Done?

- How satisfied are you with the current process you use to achieve said Job to be Done?

You may ask this for more than one job if you’ve identified or are choosing to focus on many. And in case it wasn’t obvious, you’ll replace the words “Job to be Done” with whatever term yourself and the research participant are using to describe the outcome or job in focus.

Participants will score each question from 0-10. You’ll then average the scores from common jobs and plot them on a graph like the above. This graph will give you a simple visual representation of the market opportunity a given job presents.

It’s the highly valued, underserved jobs that represent the greatest opportunity. Bottom right is what you’re searching for. This is where the greatest opportunity for new customer innovation exists.

Right now it’s important to note that some of these jobs may not be fulfilled. The customer may not yet have found a solution—even if they care about it deeply. In other scenarios, the customer may care so deeply that they’ve found their own solution. They’ve been forced to create, rather than hire from an external source.

“Know your customer—and be just a little bit humble.”

It is here that the greatest competitive insights emerge. This is where Jobs to be Done can also be used as a framework to understand your true competitive landscape. Knowing your customer and their Jobs to be Done also means knowing your competitors. They may not be who or what you expect.

As an example, you may notice that a particular job is highly valued, well satisfied, and strategically aligned to your business unit or organization’s focus. Although it doesn’t fall in the farthest bottom-right region of your graph, it piques your interest.

Upon further exploration you note that it’s not a product or service from a traditional competitor that has satisfied the job, it’s actually a hacked solution from a customer. The customer has blogged about their solution, established a community of job executors (people who have a common JTBD), and shared their solution free of charge.

If you choose to develop a proposition that fulfills this particular job, your competitor, or potential collaborator, is actually your potential customer.

These types of insights pave the way for new thinking. This new thinking paves the way for new value creation.

If you execute the 2 steps above, you’ll know your customer. Perhaps better than ever before. The outcome of this effort should be a series of well documented and understood customers jobs, along with a prioritized job backlog.

Let’s say that process took you a couple of weeks. You’ll synthesize what you’ve learned and frame hypotheses about how you can fulfill the specific job in new and unique ways.

You’ll then start a different design process. You’re going to design, test, and validate a value proposition that compels people to give you money.

But before you present your new customers with an offer, there’s another step to consider.

Will people make the switch? Will they change their behavior and adopt your new offering? This is the fundamental question. It relates directly to the efficacy of the value proposition you’ve designed, directly to how well you’ve understood the 8 job steps, and how well you’ve managed to optimize each of those steps so the success metrics your customers care about are met.

But what if you could pre-empt what they might do based on the insights you’ve already generated? What if you were better informed about what might assist people in changing their behavior? That’s where the switching model comes into the picture.

Step 3: The forces of change

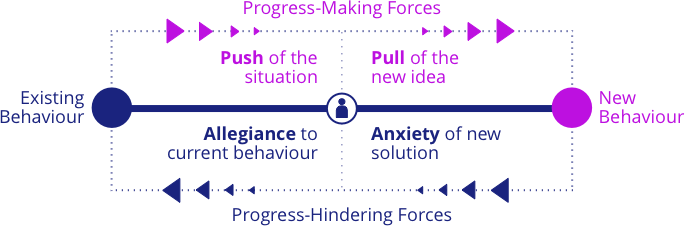

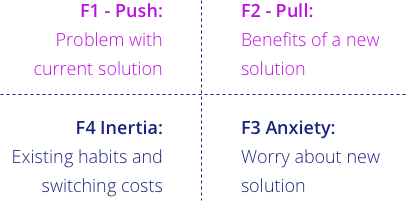

Thanks to the Re-Wired Group, the moment I’m referencing has a formula:

These are the influences impacting someone’s decision to switch. These are the forces you have to understand, design for, and do your absolute best to influence if people are to adopt the product or service you design.

Here’s the formula:

Sorry. You’re not getting my money today.

By all means, take it. My heart, mind, and wallet are open.

Once you understand these forces of change, you can begin designing pathways that encourage switching. The pathways increase progress (making forces) and limit progress (hindering forces). This is where your unique skills, expertise, and practical experience as a designer really begin to shine.

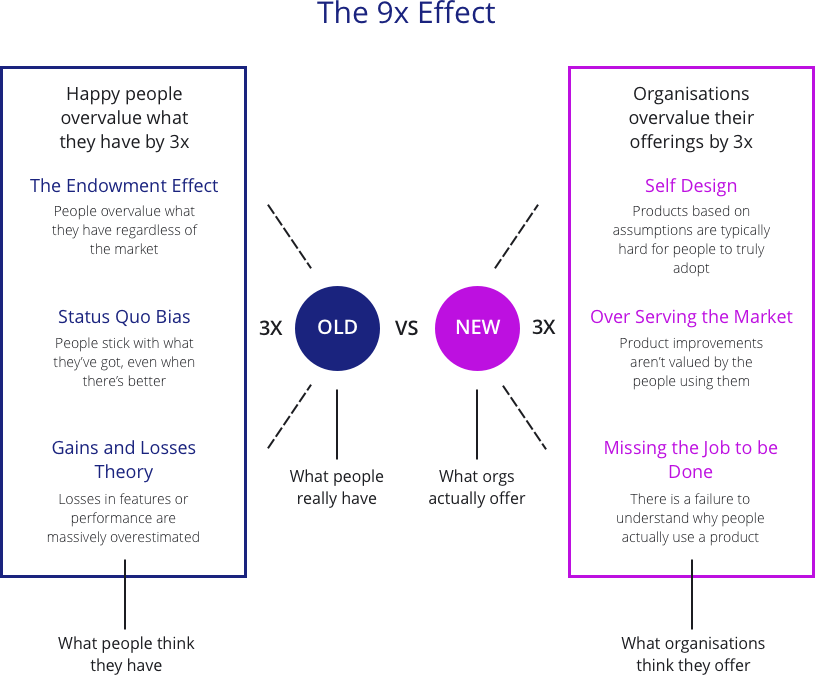

Why is Step 3 so important though? Well, you may be familiar with the 9x Effect. Basically it proposes people overvalue their current behavior, and organizations overvalue what they offer.

The sum of multiple forces on each side means there’s a lot of work to do to increase the likelihood someone makes the switch in your direction. This is why the switching moment, and the various interactions that lead to it, need to be thoughtfully designed. They need to be designed based on an intimate understanding of the customer job.

Let’s recap what we’ve covered.

- Uncovering jobs can get you closer to your customer than ever before. There’s a well documented process, with plenty of proof points to support the efficacy of this approach

- Not all jobs are created equal. Some are served well, others are served poorly. Some are deeply cared for, others are easily forgotten. Make sure you learn from your customers. Define what is highly valued yet underserved. Focus your design efforts there

- People overvalue what they have. Organizations overvalue what they offer. This decreases the likelihood someone switches to your new offering. However, you can design your way out of this by knowing your customer and being just a little bit humble

“Focus your efforts on what’s highly valued yet underserved.”

Knowing your customer is a fluid thing. The world and the people you serve are often changing. Yet the jobs they care most about rarely do. Get started with the 3 steps above. Use them to create new and unique customer value, and to competitively differentiate your offerings.